Markus Li Stensrud

Arms Around the Horse's Neck

The Skylight Hall

19.10.23 – 19.11.23

Arms Around the Horse's Neck is part of Markus Li Stensrud's long-standing investigation of the origins and legacy of modernism. Art history is used as a starting point for investigations of existential, ideological and contemporary issues. Through a collage-like approach to sculpture and installation, elements from various spheres and eras are assembled. Aesthetically, there is a battle between the minimalist and the maximalist, between the abstract and the figurative.

In the book The Modernity of Ancient Sculpture (2012), the historian Elisabeth Prettejohn explores the links between modernism and the classical antiquity, which are often viewed in a cultural-historical context as antitheses. However, Prettejohn gives the classical antiquity a central role in the birth of modernism: «It is true that the classical Greek sculpture has done more for garden design and certain dictators than for the progressive arts. But with the fragmented Greek sculptures the quite opposite can be argued». Prettejohn claims that the colonial powers’ appropriation of antique sculptures in the early 19th century, and the way in which their fragmented state was preserved when they were installed in e.g. British Museum and the Glyptothek in Munich, had a decisive importance for the development of the idea of the abstract and fragmented as an independent aesthetic branch.

A passage in a letter from Picasso to the writer Gertrude Stein, written in 1907, supports Prettejohn's point: «Walking through Louvre it all became clear. The beauty of the antique sculptures came from their fragmented state. Their expressions only heightened by the absence of an arm, a leg, a nose». Many years later, Picasso writes about the creation of Guernica, again in the form of a letter, this time to the founder of the Surrealist movement, the writer André Breton:

I painted fragments. Fragments of memories and nightmares, of violence and bodies. I was hunted by the heritage of our civilisation. And the fragmented bodies were of flesh and blood, covering our battlefields, but also of marble and blood, flooding our piazzas and museums.

«All violence deforms and abstracts, and modernism would be impossible without centuries of violence», writes political theorist Hannah Arendt in the book On Violence (1970). For her, they represent the fragmented, antique sculptures as symbols of the eternal war of the West. The deformed bodies, in their polished marble form, reflect our detached attitude towards wars we believe do not concern us. However, she finds metaphorical hope in the etchings of the 18th century artist Piranesi:

In his prisons Piranesi fuses antiquity and modernism into a metaphysical, utopian space. There's no better metaphor for art than these towering, dark rooms, filled with both personal and collective guilt, but still managing to transform the scarce sips of light into fractal beauty.

In the universe of Piranesi, where bridges give birth to new bridges, pillars to new pillars, the utopian impulse of art stands back like a light in the dark.

From about 1915, the Dadaist movement emerged, as a reaction to World War I. In an early draft for the Dadaist manifesto, the poet Tristan Tzara writes:

The western civilization must no longer be a stone-cold Greek temple, with armored men on polished marble horses. Like a wave, the horses painted on the walls of caves must come alive and wash the world clean from millenniums of logic and violence.

The title of the exhibition, Arms Around the Horse's Neck, is taken from a passage in a letter from the poet Tristan Tzara to the artist Marcel Duchamp, in which Tzara describes the philosopher Nietzsche's encounter with an abused horse. After throwing himself around the horse's neck to protect it from its owner's blows, Nietzsche is said to have broken down in tears and lost the ability to speak. Tzara concludes the letter:

Nietzsche's arms around the horse's neck are like the arches in Piranesi's prisons, carrying the western civilization on its tired shoulders. Here it all comes crashing down. We must feel and cry and reconnect across bridges and borders. This is the foundation on which we can free ourselves from the inhumane, machine-driven dictatorships and throw our arms, not around a dying horse's neck, but around the neck of a galloping wild horse, determined to throw us off and roam free.

A horse without a rider is an eternal and happy amateur.

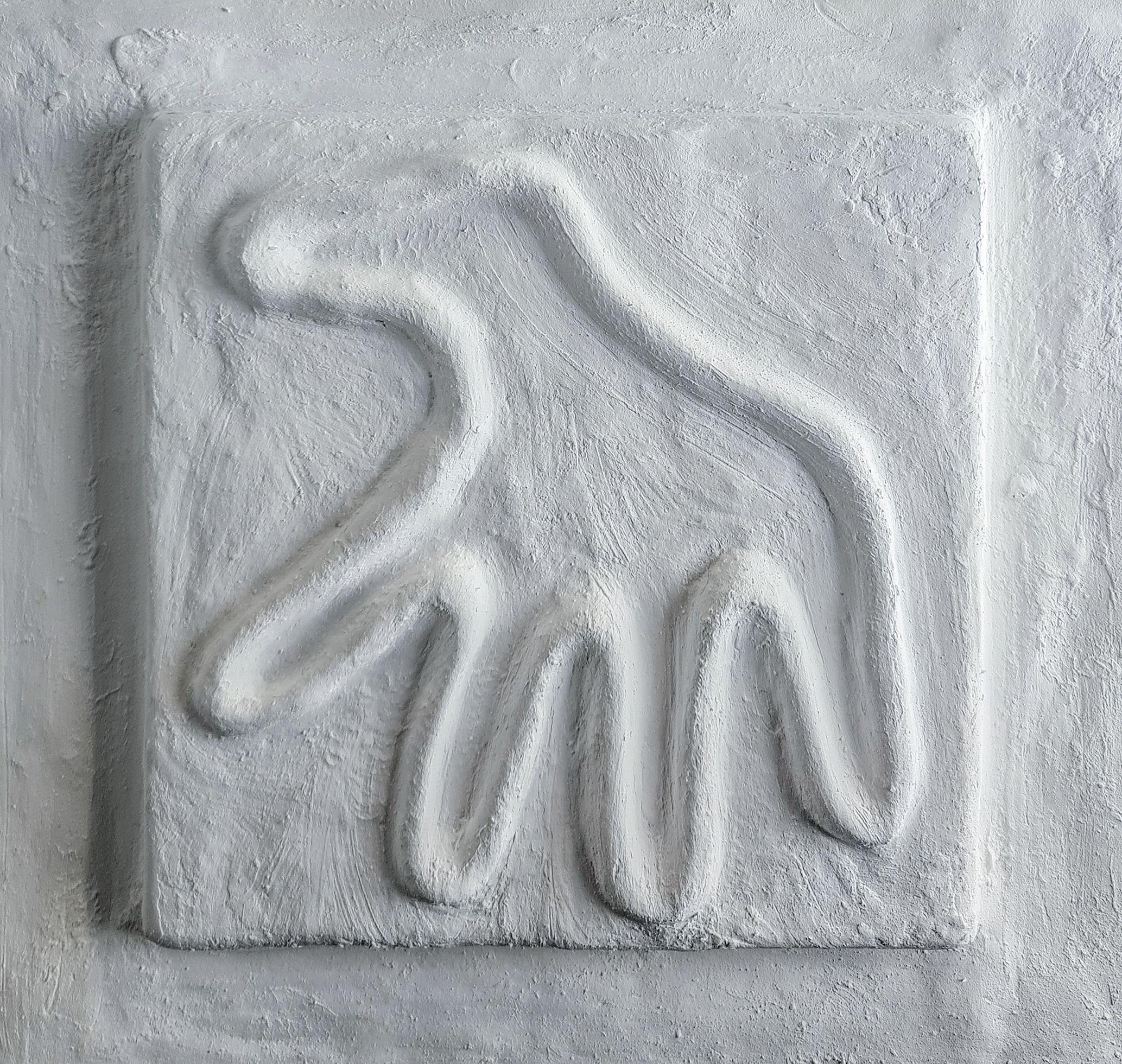

The exhibition consists of columns in plaster and reliefs in yellow wax. Hands are a red thread, along with other banal, ambiguous and universal symbols such as the horse, the sun and eggs. The exhibition balances between the epic and the ordinary, between exaltation and patheticalness. The great historical and collective lines are united with the intimate and existential.

Markus Li Stensrud (b. 1983) has a master’s degree from the Oslo National Academy of the Arts and lives and works in Oslo. Previous solo exhibitions include Contorted Mouth, Bærum Kunsthall (2020), The Extremist Banquet, Hå Gamle Prestegard (2019), The Breath of Empty Space, Elephant Kunsthall (2018), Solidified Phantoms, Kunstbanken, Hamar (2016), and Phantoms of Modernism, Kunstnerforbundet (2014). He has participated in group exhibitions such as Jeg kaller det kunst, the National Museum (2022), Vis meg din hage, Kunstnerforbundet (2019), An Account of Discovery and Wonder, Galleri 1857 (2015), En kunstner som samler kunst, Vestfossen Art Laboratory (2013), and Sparebankstiftelsen DNB NORs stipendutstilling, Oslo Kunstforening (2012).

Stensrud also does duo projects with visual artist Ida Madsen Følling. Projects include the exhibitions A Walk In the Park, Chart Art Fair with ISCA Gallery (2023), Solnedgangstider, Ølhallene, Stavanger (2023), and DOMESTISISME, Podium (2021). In 2020, they initiated the group exhibition Et Kollektivt Kaosmos at Kunsthall Oslo.

The exhibition has received funding from Arts Council Norway and the Norwegian Visual Artists Fund.